July 21, 2003

What's in a Name? In This Case, Fancy Sandwiches

![]() ONDON, July 20 "Going into trade" used to be one of the worst things an English aristocrat could do right up there with "buying your own furniture," as the late Tory politician Alan Clark, who lived in a family castle, once witheringly said of a colleague, Michael Heseltine, who did not.

ONDON, July 20 "Going into trade" used to be one of the worst things an English aristocrat could do right up there with "buying your own furniture," as the late Tory politician Alan Clark, who lived in a family castle, once witheringly said of a colleague, Michael Heseltine, who did not.

But these are strange times for the upper crust. Being a hereditary peer someone with an inherited title may get you a good table in a restaurant, but it counts for little else these days. With their money often tied up in huge country holdings that can be ruinously expensive to maintain, even members of the landed gentry are having to find new ways to earn a living.

That helps explain why the family of the 11th Earl of Sandwich has set up a sandwich-selling business, also called The Earl of Sandwich.

That helps explain why the family of the 11th Earl of Sandwich has set up a sandwich-selling business, also called The Earl of Sandwich.

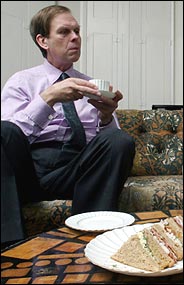

"Trading on one's family name is not derogatory anymore, at least not in my view," Lord Sandwich, 60, said in an interview in the House of Lords. He is one of the few hereditary peers who won the right to keep their seats there after most were evicted by the government in 1999.

Of his illustrious family of naval officers and lawmakers one Sandwich or another has been in Parliament continuously since the 1660's, he said the most famous is the fourth Earl. He was first lord of the admiralty and financed the expedition of Captain Cook, who kindly named the Sandwich Islands after him. (Later they became Hawaii.) He was also a bon vivant whose eureka moment, legend has it, came during an all-night gambling session, when, rather than waste time by sitting down to dinner, he ate a hunk of meat between two pieces of bread and gambled on.

Since then, Sandwiches have always been inextricably linked with sandwiches. The earl's grandfather, for instance, was known (to his chagrin) as Lord Snack. "We had a small joke that if one had a small percentage of every sandwich sold around the world, it would give us enough for a few years," Lord Sandwich said.

Beyond that, though, the family has never made too much of the connection, not eating sandwiches more often than anyone else, for instance, or taking a proprietary interest in other people's lunches at picnics. The current earl says, though, that he has long fretted from afar about the poor quality of British sandwiches, which until the early 1990's tended to consist of stale white bread filled with dubious meat or fish products smothered in gelatinous sauce.

"If you're asking me, my preference is to have a sauce that doesn't fall out of the sandwich," said Lord Sandwich, tall and sharp-eyed, with the look of a large wading bird.

In 2001, the Earl of Sandwich (the company) began delivering upscale sandwiches, made with fresh ingredients from small British producers, to businesses across London. The company also sells sandwiches to Waitrose supermarkets; the packages bear the family crest.

The idea for the company was born in 1992 when Lord Sandwich's second son, Orlando Montagu he has the right to call himself "honorable" but has no title stumbled upon a snack bar in Milan that called itself the Earl of Sandwich and used the family as its theme (weirdly for him, it even served

"I said, `Like it or not, the connection between our family and the food product has turned from being a story to a brand,' " said Mr. Montagu, who manages day-to-day operations of the business.

Early on, seeking financing, he wrote to the founder of the Hard Rock Cafe and Planet Hollywood, named, coincidentally, Robert Earl.

"His first crazy notes to me about eight years ago were infringing on the crackpot," recalled Mr. Earl, who has invested several million dollars he would not say how much in the venture. " `Dear Mr. Earl, my father is an earl and you're an Earl; I'm an Orlando and you live in Orlando let's go into business.' They were very posh, very stylized, with a beautiful signature and calligraphy, and they went right into the bin."

Similarly, when Mr. Montagu, now 32, raised the sandwich-selling issue at home, he met resistance. "I should think I was a bit hesitant to begin with, as I have no personal experience of going into business," Lord Sandwich said.

This fall, however, the company is to embark on its biggest venture yet, when it opens its first cafe, at Disney World in Florida. The plan is to offer an unusual array of hot and cold sandwiches, fillings and accouterments that will be made on the spot in a dιcor that mimics that of the earl's own home.

"We'll have three or four elements, from the living room and fireplace to the reading room," Mr. Earl said. "In this day and age it doesn't hurt to have a theme."

Profits from certain sandwiches will go to charity. Other profits will go to the earl himself and and his wife, Countess Sandwich, who run a large country estate in Dorset, which they also support partly by charging a fee to visitors.

With the government trying to devise a way to eject the rest of the hereditaries from the House of Lords, Lord Sandwich knows his days there are numbered. He tries to relish it while he can, while also moving forward.

"There's no real security in simply being from an old family anymore," he said. "Today people recognize that you're wasting your life if you're not making the best use of all the advantages you've been given."

While shopping at Waitrose, he enjoys buying Earl of Sandwich sandwiches, each of which bears his signature. It is the same signature that appears on his credit cards. Yes, the cards say "Earl of Sandwich" on the front, where the name goes.

It is as though Chef Boyardee himself had suddenly materialized, wearing a suit and speaking the Queen's English, and trying to buy his own products.

"The cashiers are astonished when they see my cards," Lord Sandwich said. "I think it's quite a good marketing ploy."